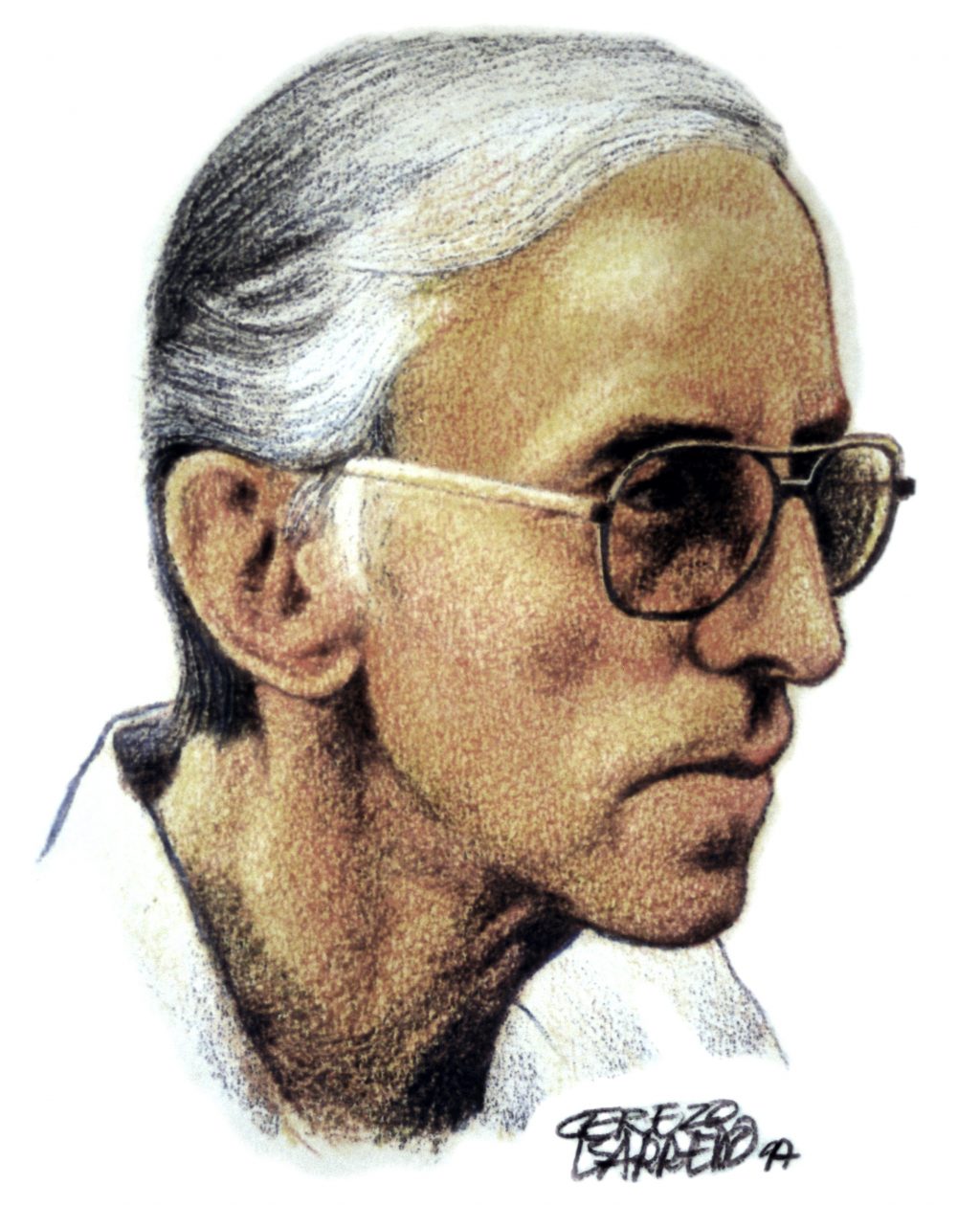

A tribute to Bishop Pedro Casaldàliga

(1928-2020)

Fr. Paulson Veliyannoor CMF

Your miter will be a straw hat. Your staff will be the truth of the Gospel. Your ring will be the New Covenant of the Liberating God and the Faithfulness to the people of this land. Your shield will be the strength of Hope and the freedom of the children of God. Your gloves, the service of Love.

The above words formed the mandate a catholic bishop demanded of himself and made clear at his consecration, a promise and pledge he fulfilled throughout his 34 years of active episcopacy; the defining marks that would characterize his episcopate and missionary life.

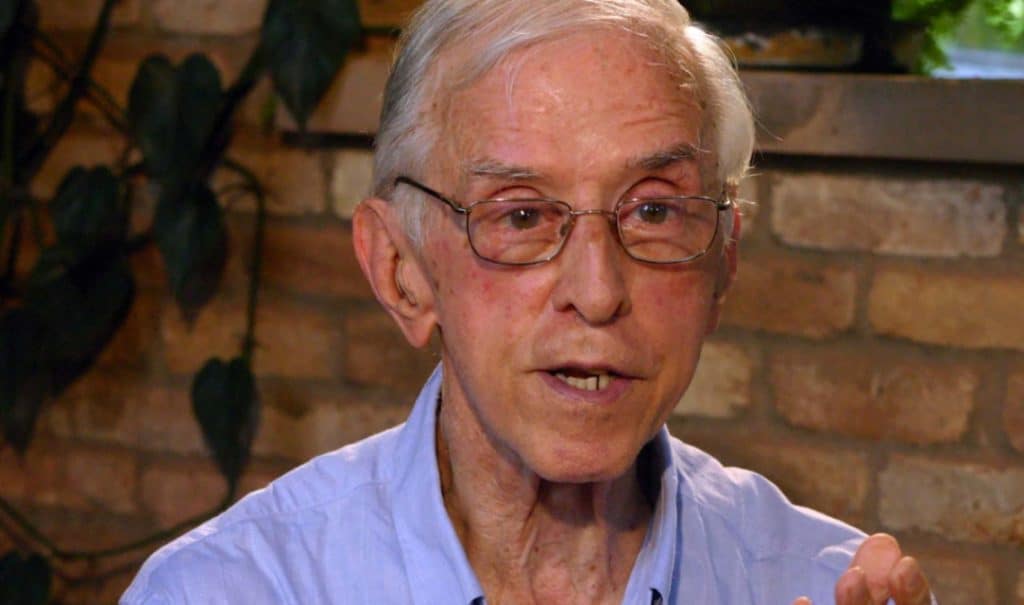

Bishop Pedro Casaldaliga

Pedro Casaldàliga, a Claretian missionary and bishop emeritus of the Amazonian territorial prelature of São Félix do Araguaia in the state of Mato Grosso in Brazil, died on 8 August 2020, at the age of 92: the final rite of passage for a life that has touched million lives.

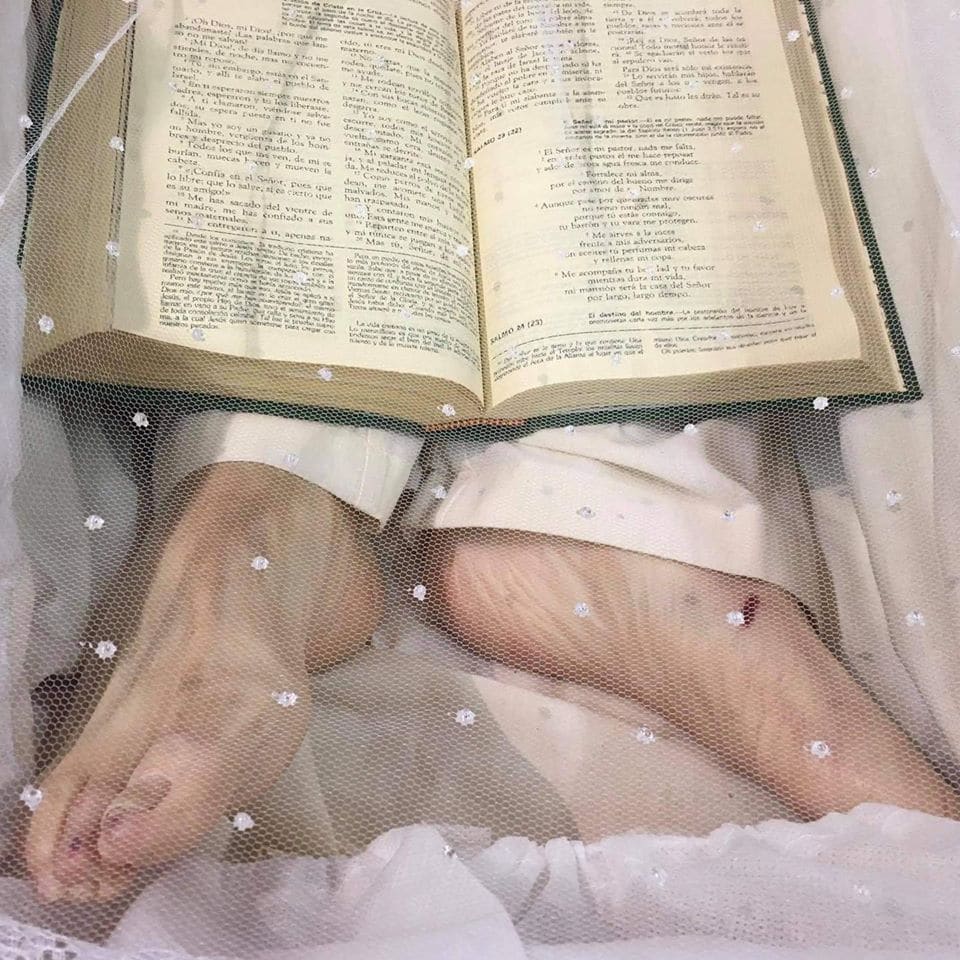

The sight of bishop Casaldàliga lying in state in a simple wooden coffin is a window to the soul of the man and sums up his entire life: an open Bible placed above his bare feet.

Indeed, he was a man on his feet, fired with the gospel, who walked the Latin American earth to serve, care for, and defend the rights of God’s children. He fought for the earthly rights of the indigenous people, especially of Xavante Indians, of Amazonian Brazil. As he once wrote, “the earth is the only path that can lead us to heaven.”

Formative Years

Pere Casaldàliga i Pla was born on 16 February 1928 in Balsareny in Catalonia in Spain into a devout catholic peasant family. His childhood was marked by the experience of revolution and religious persecution of 1936. He knew what it meant to be a persecuted Church; but he would remark years later: “Later I understood better to what extent conflict must be an essential part of the Church and of the life of Jesus Christ.” He wanted to be part of that Church, caring for the soul and the body of God’s children. As a young boy, one day he threw himself on his mother’s neck and cried, saying, “I want to be a priest, mother.”

“How beautiful are the feet of those who bring [the] good news!” (Romans 10:15)

The Body of Bishop Pedro Casaldaliga lies in state with an open Bible

placed on his bare feet

At the age of 12, he entered the diocesan seminary at Vic. Later, at the age of 17, he joined the congregation of the Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (a.k.a. Claretian Missionaries) at Vic. The next 12 years of formation would firm up his native resolve and fire to create a revolution from within and dedicate his life totally for God and His people. Ordained at the age of 24 in 1952, he would spend the next 16 years in Spain, ministering at various locations such as Sabadell, Barcelona, Barbastro, and Madrid. He was already earning a name as a firebrand missionary who defended the cause of the poor: In the shanty towns of Sabadell, he became a voice for the workers’ rights, much to the discomfort of the regime.

Destiny Calls: To the Amazonian Fields of Brazil

In 1968, his congregational superiors assigned Pedro to Brazil, to open a new mission in Mato Grosso, in the middle of the Amazon. Those were the years marked by the refreshing yet challenging reforms of the Second Vatican Council as well as the most violent phase of military dictatorship in Brazil. In response to such ambience, the strong wind of the Theology of Liberation was emerging in Latin America. It was an assignment that had a perfect goodness of fit for the personality and vocational fire of Pedro Casaldàliga. And how it found its fruition in Brazil! He left Spain in 1968, and though he would write a poem titled “I still breathe in Catalan” (Todavía hoy respiro en Catalán), he would never ever return to his fatherland, even when his mother died. He pitched his tent, with Christ, in Brazil, until his last breath.

Pedro soon plunged into incarnating himself as one among of the natives in Mato Grosso, who had been suffering extreme deprivations and poverty forced on them by the landlords and the military regime. Pedro would soon create a church network from the scratch and organize them into communities of faith and social action to defend their own rights. In 1971, Pope Paul VI appointed him the first prelate of the newly created territorial prelate of São Félix do Araguaia. Pedro resisted the move, but accepted it finally as the will of the people and God.

In Defense of the Poor and the Natives

As the bishop, he committed himself to be a true father and defender of his people.

His very first pastoral letter, An Amazonian Church in Conflict with the Latifundia and Social Marginalization, would set the tone for the remaining years of his episcopate. As a bishop, he operated from a small, poor, rural house, living like one of his own flock. Casaldàliga was one of the founders of the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI) and the Pastoral Commission of the Land (CPT), two major religious undertakings in Brazil, which have played a significant role in the transition to democracy and in the elaboration of the 1988 Constitution, which guaranteed rights for the indigenous people.

The “Cathedral” of the Bishop!

The Chapel of the Bishop Casaldaliga

The powerful landowners, in collusion with the military regime, threatened him with death, which failed to deter him. In October 1976, an assassination attempt on him mistakenly led to the murder of Father João Bosco Burnier, who was standing next to the bishop. [The story goes that the killers failed to recognize the bishop who was a lean figure clad in plain clothes like any other person and did not have the “gravitas” of a bishop; and they mistook Fr. Burnier to be the bishop and shot him to death.]

The threat to his life never ended with the end of the military regime. Even in 2012, seven years after his retirement as a bishop, when he was 84 years old and suffering from Parkinson’s disease, he was forced to leave his home in São Felix and be moved to an unknown location for months, in the face of threats from the land mafia.

Conflicts with the Vatican

If Pedro Casaldàliga was the town’s bishop for his admirers and a red bishop for his enemies, he had a mixed reception by his ecclesiastical superiors. Pope Paul VI, who named him bishop, was a staunch supporter of Pedro so much so that when the murder attempt on him became known, the Pope publicly declared thus, in defence of Casaldàliga: “Whoever touches Peter, touches Paul.”

However, the cautionary and even prohibitive stance by the Vatican towards liberation theology, fearing that it might derail into violent activism, led to some tensions between the bishop and Pope John Paul II and Cardinal Ratzinger (later, Pope Benedict XVI). Casaldàliga refused to sign a document accepting restrictions on his theologizing and style of pastoring, while also affirming that he is in communion with Rome, but wanted less centralism and more space for women, collegiality, and dialogue within the Church. His refusal to make mandatory ad limina visits to Rome in the 1980s was more out of a fear of being prevented by his enemies from re-entering Brazil once he traveled outside. But he also felt that the ad limina visits were more of a bureaucratic formality, which did not excite him much.

Casaldàliga wanted the Church to leave her safe walls and walk into the midst of the people and feel the pulse of life – a theme Pope Francis would later give voice to. Pope Francis would consult him while drafting his encyclical Laudato si’ and quote from his poem in his Querida Amazonia, the post-synodal apostolic exhortation on Amazon. Pope Francis seems to be putting into action what Casaldàliga boldly called for in a poem, at the news of the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI, dreaming of a Church that is more revolutionary in every gospel sense of the word (see the poem “Leave the Curia, Peter” in the box). Over the course of his life, Casaldàliga received many awards; but many believed that he deserved to be made Cardinal. It never happened. Not that he cared in the least.

All-in-One: Lover, Poet, Rebel, Missionary, Mystic

Casaldàliga was a multifaceted personality. Primarily, he was a lover, his first love being God, and then came Mother Mary. If Jesus with his gospel was everything for which he lived, Mary was his mother, the woman he was in love with. He cherished his religious identity as a Claretian whom his congregational founder, St. Anthony Mary Claret, had defined as “a son of the Immaculate Heart of Mary.” He was also fired by the martyrdom of the 51 young Claretians in Barbastro in 1936. The martyrial dimension of his congregational charism impelled his feet to be a missionary in a faraway land. He was very fond of his fellow bishop Oscar Romero who was martyred for denouncing violence and defending the rights of the poor, and whose relic he kept very reverentially with him. He used to call him Saint Romero of America, even before his canonization.

As Fr. Pedro Belderrain, major superior of the Claretian province of Santiago (Spain) wrote in his homage, Casaldàliga would say: “Don’t look at me; look at Jesus. And look at him a lot, but immediately, without wasting time, look at the brothers.” After Jesus and Mary, his next love were people whom he met, with the indigenous people of his adopted land having a very special place in his heart. He was a rebel, but rebel in the mould of Christ. As Casaldàliga wrote, “everything is relative, except God and hunger.” Therefore, “it is not enough to be a believer. You have to be credible.” His way of being credible was by living the cause of the Gospel. For, as he observed, “if there are no great causes, life has no meaning.” He was convinced that “most of humanity today survives rather than lives.” But because “in love, in faith and in revolution, neutrality is not possible,” his greatest wish was “an end to hunger in the world, an end to the manufacture of weapons, an end to the arms race, an end to war, especially war for religion or supported by religion.”

Such dream made him a poet and mystic as well. He has left behind around 50 works of prose and poetry. We have already sampled a few of his poems. He was another John of the Cross, but “a Guerilla John of the Cross,” as José I. González Faus would title his eulogy of the bishop. For, Casaldàliga, mysticism was one of pure love of God in and through the committed defense of his people. He wrote thus:

At the end of the road they’ll ask me: – Have you lived? Have you loved? And I, without saying anything, will open my heart full of names.

Legacy of his Life and Death

Casaldàliga embraced life and its challenges in active and passive ways. In the final decade of his life, he was hit by Parkinson’s disease (whom he called “my brother Parkinson” and “my superior general, because I always do what he orders me to do”). He embraced whatever suffering that came his way, from within and without. For him, prison and illness are two more sacraments, as he once observed. He lived a simple, but profoundly impactful life, a life that has changed the destiny of his people. As José Manuel Vidal wrote in his memoriam, in touching him, people felt they were touching the flesh of a saint.

As he lived simply, he wanted to die simply as well. For years, his health had been declining and the keen interest in him even led to false reports of his death a few years ago. On 4 August 2020, he was admitted to hospital for respiratory problems. He died peacefully four days later.

While alive, Casaldàliga had expressed categorically his desire for a simple burial in an unmarked, earth-friendly ambience. “My causes are worth more than my life,” he had said. His wish was respected. He had a simple casket. He was laid with bare feet and a Bible on them. He was buried on 12 August, in an extremely simple earthy tomb, under a tree in an open field, under the symbol of a simple cross. As Fr. Gonzalo Fernández Sanz, vicar general of the Claretians, observed, he is buried in the humble cemetery of the Karajá Indians, on the banks of the Araguaia river, between the graves of a farmhand and a prostitute, on red soil, teaching us how to be a model of a Church “from below.” So fittingly symbolic of his life. For, he identified himself thus:

“I, sinner and bishop, confess of dreaming of the Church dressed only in gospel and sandals.”

He was buried on 12 August, in an extremely simple earthy tomb, under a tree in an open field, under the symbol of a simple cross. He is buried in the humble cemetery of the Karajá Indians, on the banks of the Araguaia river, between the graves of a farmhand and a prostitute, on red soil, teaching us how to be a model of a Church “from below.”

By no means was Casaldaliga a perfect man. He had his share of human frailties. Not everyone shared his convictions and methods. But there is no denying that he loved God, the Church, and the people, setting us an example of how to be a Church. Barefoot on the Red Earth (Descalzo sobre la tierra roja) is the name of the movie that was made on his life in 2013.

He was exactly that, as he mandated himself at his episcopal consecration. And, now he is inside the earth, buried barefoot with the subversive peace of the Gospel. He had said, “I will die standing up like the trees.” Quite fittingly, he lies buried beneath a tree. His earthly body will fertilize the Brazilian land; and his fiery spirit must fertilize our hearts, fighting for his cause, the cause of the Gospel at the service of God’s children on the margins.

| “Leave the Curia, Peter!” (English translation of Casaldaliga’s poem, ‘Deixa a Cúria, Pedro!’, originally written in Portuguese.) Leave the Curia, Peter, disassemble the Sanhedrin and the walls, order all the impeccable scrolls to be changed to words of life and love. Let us go to the garden of the banana plantations, undercover and by night, at any risk, for there, the Master sweats the blood of the poor. The tunic/vestment is this humble disfigured flesh, so many cries of children unanswered, and memories embroidered with the anonymous dead. A legion of mercenaries besieges the frontier of the rising dawn and Caesar blesses them in his arrogance. In the tidy bowl, Pilate, legalistic and cowardly, washes himself. The people are just a “remnant”, a remnant of hope. Leave them not alone among the guards and princes. It’s time to sweat with His agony, It’s time to drink the chalice of the poor, lift the cross, devoid of certainties, shatter the building — law and seal — of the Roman tomb, and wake up to Easter. Tell them, tell us all that the grotto of Bethlehem, the Beatitudes, and the judgement of love as food, remain in force and steadfast. Be no longer troubled! As you love Him, love us, simply, as an equal, brother. Give us, with your smiles, your new tears the fish of joy, the bread of the word, roses of embers … … the clarity of the untrammeled horizon, the Sea of Galilee, ecumenically open to the world. |