There was something unusual about the crib on display in the compound of Sacred Heart Cathedral in Mandalay on Christmas Eve. Instead of the familiar western faces and Middle Eastern garments, Joseph and Mary had Asian features and wore traditional Burmese clothes, as did the shepherds and kings who came to worship baby Jesus.

It was an initial step to introduce inculturation to Catholics and followers of other faiths in the Buddhist-majority country in 2002 led by Archbishop Marco Tin Win of Mandalay, at the time a priest in the Archdiocese of Mandalay.

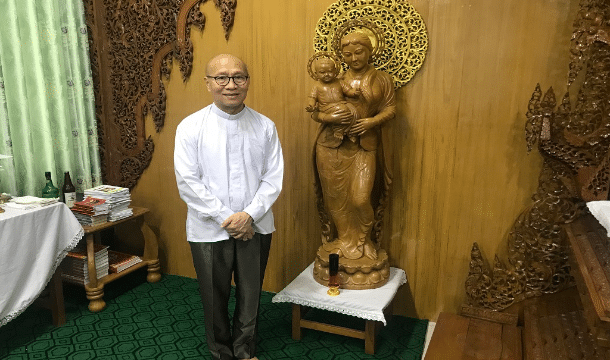

With the help of a Buddhist artist, the archbishop had Burmese-style wooden statues made. He realised he needed to carry out inculturation when he was seeking interreligious dialogue, especially in meetings with Buddhists.

“The way we speak and the way we worship are different from Burmese culture, so we are like strangers to other people. I got the idea from carrying out interreligious dialogue and visiting Buddhist monasteries,” he said.

Archbishop Tin had intended to write a book about inculturation after his return from further studies in Rome in 1997, but most of his time was spent on interfaith activities and writing books about interreligious dialogue. The book on inculturation was finally published in 2015.

He recalled that no one had heard the term interreligious back in 1998. It’s a strange word among the Catholic community, so he started to write a book about interreligious dialogue.

While introducing inculturation in the Church in Myanmar, the archbishop had his head shaved as Buddhist monks and nuns do as a symbol of giving up worldly attachments.

As an initial step, he tried to focus on language and body language in liturgical services. “If the way we use words and the way we worship are not in line with the cultures and traditions, people from other faiths will always see us as foreigners,” he said.

We are not foreigners

During an interview in the archbishop’s house in Mandalay, Archbishop Tin elaborated on his efforts of inculturation one step at a time such as language, a Burmese-style crib and images of Mary in traditional Burmese clothing.

His 18-year journey has not been smooth and he has faced many challenges, even including resistance from fellow priests.

“Laypeople and clergy from Mandalay were uneasy when I started to display the crib with Burmese features as they presumed it is the way of Buddhism,” the 60-year-old archbishop said.

“People thought I might be converted to Buddhism. I had a shaved head and frequently visited monasteries. We are not imitating Buddhism, rather we are trying to embrace our own culture and announcing gospel values.

“In Myanmar, Buddhism has totally embraced the culture and traditions of Burmese, so we can’t easily separate religion and culture. If we don’t embrace our own culture according to the teaching of the Church, we Catholics will remain strangers to others.

“Once we embrace our own culture after understanding its essence and values, we may have success in the mission of evangelisation and interfaith dialogue.

“My goal is to show that we are Burmese Catholics, Kachin Catholics, Karen Catholics and we are living in Myanmar. We are not foreigners.”

Patience and perseverance

Besides writing books, Archbishop Tin has been giving awareness training about interreligious dialogue and inculturation in dioceses across the country. In some dioceses, people from ethnic communities thought he was promoting Burmese culture.

“I try to explain to them that as I’m a Bamar, I use Burmese culture as an example. Each ethnic group need to do it with their own culture,” the archbishop said.

He said dialogue with religions, cultures and the needy is the vision of the Archdiocese of Mandalay.

He acknowledged it is a long journey, but Catholics need to make preparations for the people, educate the people and move on slowly. With patience and perseverance, the effort has been welcomed by most people.

“As a bishop, I get a chance to continue my mission, but I’ll go on lowly as it takes time,” he said.

At the highest level of inculturation, the archbishop has also taken a move on silence, solitude, meditation and contemplation. “As it is an embedded tradition among people in Myanmar, most people can easily accept them despite the deeper level.”

He said dialogue with religions, cultures and the needy is the vision of the Archdiocese of Mandalay.

Archbishop Tin has a strong commitment to interfaith harmony and has carried out projects with Buddhists, Muslims and Hindus.

He is head of the Episcopal Commission for Interreligious Dialogue at the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Myanmar. He also served as secretary of the commission for several years.

He was among the Asian bishops Pope Francis appointed as new members of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue in July