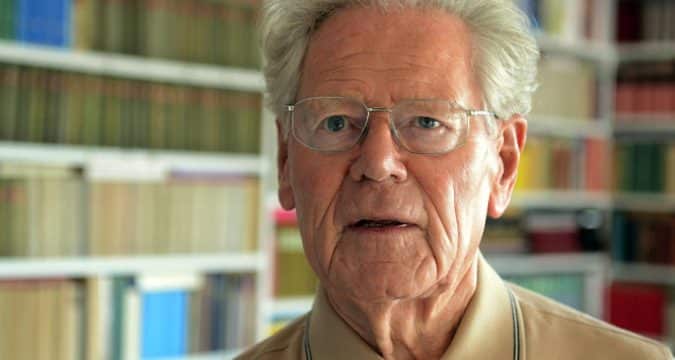

VATICAN (Agencies): Swiss Father Hans Küng, often perceived as a critic of the Church and sometimes going beyond Catholic doctrine and criticising the decisions of Church leaders, died on April 6 in Tübingen, Germany, where he lived and taught for decades. He was 93-years-old.

Father Küng was born 19 March 1928, in Sursee, Switzerland, was a prolific writer and wrote several bestsellers that were translated into more than 30 languages. He was one of the most outspoken Roman Catholic theologians and one of the sharpest critics of Pope St. John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI—the latter a friend with whom he had studied and worked at the University of Tübingen, Germany, in the 1960s, UCAN reported.

He frequently criticised papal infallibility as outlined by the First Vatican Council, mandatory priestly celibacy, the loss of the Church’s credibility, the ban on women priests and took aim at what he called the “Kremlin-like” Roman Curia and called for greater democracy in the Church.

In 1979, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith revoked his faculty to teach as a Catholic theologian, but he continued to work as professor emeritus of ecumenical theology, Vatican News reported.

In a 2005 article, the Sunday Examiner (9 October 2005) noted that during a 2005 meeting with Pope Benedict, not long after his election to the pontificate, Father Küng’s efforts to contribute to a renewed recognition of humanity’s essential moral values through the dialogue of religions and through an encounter with secular reason were recognised by his friend, who also paid special tribute to his work in creating a “global ethic” based on what he saw as the shared principles of major faiths for which he was honoured with the Niwano Peace Prize in Tokyo on 22 July 2005.

Father Gianni Criveller of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions, writing in UCAN, called Father Küng a great contemporary theologian and intellectual. He noted that the theologian was a self-assured man full of charm and much admired who also paid particular attention to China and its religions having explored themes of interreligious dialogue which led to the development of the Global Ethics (Weltethos) project.

Father Gianni Criveller of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions, writing in UCAN, called Father Küng a great contemporary theologian and intellectual. He noted that the theologian was a self-assured man full of charm and much admired who also paid particular attention to China and its religions having explored themes of interreligious dialogue which led to the development of the Global Ethics (Weltethos) project.

Father Criveller writes of Father Küng’s co-author on the book, Christianity and Chinese Religions, the late Julia Ching, known for her expertise on neo-Confucianism and religion of the Song and Ming dynasties of 10th- through 17th-century China and her studies of the leading Ming Confucian, Wang Yangming, and the leading Song Confucian, Zhu Xi.

Father Criveller notes that the two shared a bitterness about the injustice and dullness they suffered from the institutional Church, among other things, with Ching having left the consecrated life, leaning to Buddhism and speaking reluctantly of God. However, Father Küng—who never left the priesthood—was critical of Buddhism’s focus on suffering and on the negative things in life, and reminded Ching of the fundamental trust of Christians in Jesus, telling her: “I prefer Christianity, a religion of revelation. We (Christians) try now to reduce suffering in the world. We believe in Christ as the victor over death and destruction.”

Others who knew and worked with him described Father Küng as a man who loved the Catholic Church. Cardinal Walter Kasper of Germany, retired president of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, told L’Osservatore Romano, that Father Küng was a person who knew deep in his heart that he was Catholic and never left or wanted to leave the Church, even if “his behaviour” was not always that of a Catholic.

In the interview published on April 7, Cardinal Kasper spoke about having served as a doctoral assistant to Father Küng from 1961 to 1964, before a long period of distance and deeply diverging views on a host of theological questions and the proper way to raise them.

But in the past few decades, the cardinal said, their relationship was one of mutual respect. “Certainly, the theological differences remained, but on a human level, the relationship was straightforward and peaceful,” he said.

Father Küng was more than a critic of the Church “he was a person who wanted to promote renewal of the Church and realise its reform,” the cardinal said, adding, however, “In my judgment, he went too far—beyond Catholic orthodoxy—and so did not remain tied to a theology based on the doctrine of the Church, but ‘invented’ his own theology.”

Cardinal Kasper said he found “unacceptable” the way Father Küng had sometimes spoken about Pope Benedict XVI, with whom he had served as an expert at the Second Vatican Council, but “I know Benedict prayed for him.”

Father Küng was more than a critic of the Church ‘he was a person who wanted to promote renewal of the Church and realise its reform,’ the cardinal said, adding, however, ‘In my judgment, he went too far—beyond Catholic orthodoxy—and so did not remain tied to a theology based on the doctrine of the Church, but ‘invented’ his own theology’

Nevertheless the cardinal said Father Küng always was ready to talk, discuss and debate, and he knew how to write and talk about religion in a way that was understandable to people who were not Catholic or had moved away from the Church. He also was a pioneer in ecumenism and interreligious dialogue.

Near the end of his life, Father Küng drew close to Pope Francis, the cardinal said.

“Last summer I phoned the pontiff to tell him that Küng was near death and wanted to die at peace with the Church. Pope Francis told me to pass on his greetings and his blessing,” Cardinal Kasper recounted.

“Certainly, the theological differences remained and were not resolved,” the cardinal said. But “on a pastoral and human level, there was a reconciliation.”

Cardinal Kasper said, “He wanted to die at peace with the Church despite all the differences.”

Bishop Georg Bätzing of Limburg, president of the German Bishops’ Conference, said, “Hans Küng never failed to stand up for his convictions. Even if there were tensions and conflicts in this regard, I thank him expressly in this hour of parting for his many years of commitment as a Catholic theologian in communicating the Gospel. The dialogue of religions in the quest for a global ethic was of great concern to him. Hans Küng was deeply influenced by the Second Vatican Council, whose theological reflection he sought.”

Although he taught in Tübingen, Father Küng remained a priest of the Diocese of Basel, Switzerland. Bishop Felix Gmür of Basel, president of the Swiss Bishops’ Conference, said that for all his criticism, “Hans Küng was a lover of the Church.”

Bishop Gmür said, “He did not want to make the Church superfluous and did not want it to perish. He wanted a renewed Church, a Church for today’s people.”

The bishop said, “He fought for a Church that would deal with the realities of life as they are and with the world as it is. He wanted a Christian Church and a Christian faith and people of Christian faith who listen and are heard, with whom one can discuss, who get involved, who live out of their trust in God, who serve peace together with other believers.”

He said, “That is why he dealt with the Church as it is. He did the same with me, his bishop. He loved, and because he loved, he demanded. That could sometimes also be exhausting. This was experienced by some with whom he did not hold back with criticism, especially the popes.”

Bishop Gmür said he was sometimes surprised by the way Father Küng “positively stood by the papacy despite all his struggles.”