This is the second in a series of articles covering the origin and development of the Diocesan Justice and Peace Commission since its inception

HONG KONG (SE): “As Children of God, we need some spare room for ourselves to take a rest and do some personal reflection. While the wilderness is a good place to pray, it seems to be a luxury in modern society. We can only set up an area for ourselves to relax and reflect in this overcrowded environment, as property prices is several hundred dollars per square feet!”

This is part of an article written by the Justice and Peace Commission of the Diocese of Hong Kong in a column in the Chinese-language diocesan weekly, Kung Kao Po, in 1978, concerning Hong Kong’s housing problems and how it could hinder integral human development which, according to Pope St. Paul VI’s 1967 encyclical, Populorum Progressio [On the Development of Peoples] should ensure a full improvement for all and address the human need “to enjoy higher values of love and friendship, prayer and contemplation” [20].

The commission, to be renamed Diocesan Commission for Integral Human Development at the end of 2022, was set up in January 1977 in response to the social concern mission mentioned in the above encyclical, which emphasises integral human development as the goal of the mission of the Church.

The commission was also inspired by the teaching of the 1971 Synod of Bishops on Justice in the World, which urges the Church to help remove unjust social structures.

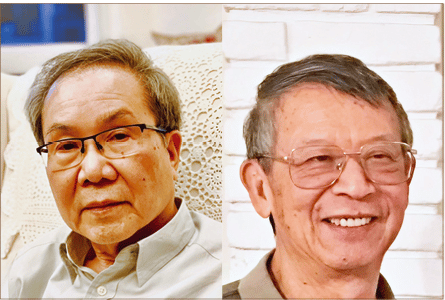

The commission’s first chairperson was Andrew So Kwok-wing, an educator and later an unofficial member of the Legislative Council in 1978.

The Church had to be able to read the signs of the times. We are not political parties. The basis of our response to social injustice is our faith. We aim at peace, and there is no peace without justice

Peter Cheung Ka-hing

Peter Cheung Ka-hing, the first vice-chairperson of the commission, recalled that it was set up while the whole Church, in line with the Second Vatican Council, was reconnecting herself to the deposit of faith and rediscovering the true meaning of human existence and the mission of the Church in the world as the People of God.

Cheung also expressed his appreciation of Bishop [later Cardinal] John Baptist Wu Cheng-chung, who was then bishop of Hong Kong and who was very encouraging and supportive about the idea of setting up a Diocesan Commission for Justice and Peace, after the Pontifical Commission for Justice and Peace was set up in Rome in 1976.

Cheung was also of the view that the commission was set up at the right time. There was room for such an initiative in Hong Kong in the 1970s. With Sir Murray Maclehose as governor, there was more room for social expression, including social criticisms and protests.

Along with the development of public housing and the resettling of people from squatter areas and temporary housing, there were also more social justice issues that called for attention from civic and Church groups.

“The Church had to be able to read the signs of the times. We are not political parties. The basis of our response to social injustice is our faith. We aim at peace, and there is no peace without justice,” Cheung said.

We tried to express our views according to Catholic social teachings, raising the awareness of people on these issues and bringing them to the attention of our society as a whole and of those in power

Peter Cheung

He remembered that one of the concerns about labour rights at the time was protecting workers’ rights to rest from their daily work. The issue was annual paid leave. One of the commission members was Jesuit Father Patrick McGovern, who was also an unofficial member of the Legislative Council.

Having a law passed guaranteeing seven days’ annual leave with pay was a step forward in social justice, and here the Justice and Peace Commission played a part.

“We tried to express our views according to Catholic social teachings, raising the awareness of people on these issues and bringing them to the attention of our society as a whole and of those in power,” Cheung said.

To mark the 10th anniversary of Populorum Progressio, seminars were held for lay people to illustrate why integral human development was important to the people of Hong Kong as well as to people in other parts of the world.

The commission also translated the encyclical into Chinese and gave simple explanations and analyses of related situations in Hong Kong in articles published in the Kung Kao Po.

As an early member of the commission, [Andrew] Wong [Kam-cheung] was concerned whether the government could provide sufficient personal space and facilities for public housing in the 1970s, which could impact emotional health and put families under stress

Cheung said he felt happy to join the commission so that he could live his faith more fully with people who shared a similar vision. “We became even more aware that we are driven by our faith to live not just for ourselves. And, in living for others, our lives are enriched. We experienced a little of what it means to live by aiming at integral human development,” he said.

He recounted that the views of commission members were divided at times, which could be a good thing, as it could help to ensure that their public statements would be more objectively made after taking different aspects into account. Unfortunately this did not always happen.

In late 1977, students of the Precious Blood Golden Jubilee Secondary School held protests expressing concerns over the unclear financial records of the school discovered by teachers. This led to its closure, announced by the Education Department in May 1978.

In this incident, he remembered that some commission members tended to have more empathy with teachers and students, while some took the view of the establishment. “The problem was not about differences,” he said, “it was more about the inability as a group to deal with the differences.”

Looking back, Cheung felt deeply that there is a lesson here to be learned. “As it should be, members of the commission came from different strata of society. Conflicts that arise in society are expected to be reflected in some way in the commission. But we share the same faith, and that is our uniqueness. We might belong to different social groups and shared their perspectives. But here in the commission, we look at issues from the perspective of integral human development, enabling us to be more focused, more humble, and more disposed and determined to listen to each other.” Cheung said.

…it is an important part of integral human development to give everyone an equal chance to attain better living standards. ‘The responsibility of a government is to come up with visionary plans for housing instead of responding to current needs

Andrew Wong

“If I could do this again, I’d definitely do it differently,” he added.

Cheung worked at the Catholic Marriage Advisory Council when he joined the commission. Previously he had joined a task force formed by Bishop Wu to look into how the commission could be established.

He was later the executive secretary of the Catholic Institute for Religion and Society from 1986 to 1996, and the editor-in-chief of the Kung Kao Po from 1996 to 1999. In recent years, he started an NGO called Life Inhering Association for Family Heartfelt Reconnecting, mainly involved in training related to personal and relational reconnecting, especially at the end of life.

Andrew Wong Kam-cheung was among the 11 first members of the commission. He recalled that he was a teacher involved in educational action groups and he was especially concerned about excessive public examinations and the pressure this placed on students at that time.

He has been engaged in education over the past decade, and was the head of the Department of Education of the University of Hong Kong before he retired.

…we appreciated the quick reaction of the government which resolved chaos among the police force. Peace is thus restored

Andrew Wong

As an early member of the commission, Wong was concerned whether the government could provide sufficient personal space and facilities for public housing in the 1970s, which could impact emotional health and put families under stress.

He said that it is an important part of integral human development to give everyone an equal chance to attain better living standards. “The responsibility of a government is to come up with visionary plans for housing instead of responding to current needs,” he said.

He remembered one thing the commission was happy to see at that time was the quick response of the government in resolving conflicts between the police and the Independent Commission Against Corruption [ICAC] at the end of 1978. Such a response ensured peace in society and fighting corruption at the same time.

Tensions had built up in a police force tainted by corruption after the ICAC was set up in 1974. In October 1978, angry police stormed into the ICAC offices in Central and assaulted the anti-corruption officers, threatening to escalate their actions. The situation ended with the announcement of a partial amnesty for minor corruptions committed before 1977.

At the same time, the government amended the law, allowing police officers to be dismissed at once if they did not cooperate with the anti-corruption investigations.

Wong recalled that Father McGovern kept the members updated of the development of the incidents at meetings. “We issued a statement to the governor at once after the government announced the amnesty and the law amendment as we appreciated the quick reaction of the government which resolved chaos among the police force. Peace is thus restored,” Wong said.