by John Singarayar SVD

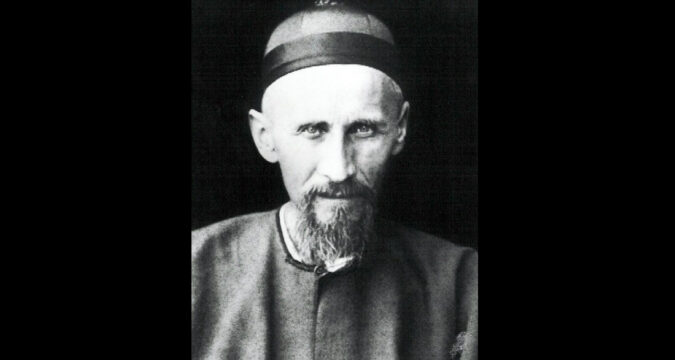

When St. Joseph Freinademetz, the first missionary of the Society of the Divine Word, whose feast is celebrated on 29 January, stepped off the boat in China during the 1870s, he carried more than luggage. He brought the unexamined certainties of a European priest who assumed he understood exactly what these people needed. The Chinese, he had been taught, were backward and morally confused, a civilisation waiting for Western enlightenment. Within months, everything he thought he knew had collapsed. Watching Chinese families navigate life with grace, witnessing their moral sophistication and ancient wisdom, he faced an uncomfortable truth: he was the one who needed educating.

This was not a polite adjustment of perspective. It was a complete dismantling of his worldview, the kind that leaves you fundamentally different than before. Freinademetz did not just learn to appreciate Chinese culture from a respectful distance. He dived in completely, spending years mastering a language that twisted his tongue, adopting clothing that felt strange on his body, eating food that initially unsettled his stomach, and submitting himself to daily rhythms utterly foreign to everything he had known. His neighbours eventually stopped seeing him as that foreign priest and started calling him Fu Shen Fu, one of their own. This was not performance or strategy. It was love made visible through the costly choice to belong rather than observe.

What separated Freinademetz from countless other missionaries was his radical conviction that Christianity did not need to destroy Chinese culture to take root there. While his contemporaries were busy trying to turn Chinese converts into European replicas, he was asking a more dangerous question: what if the Gospel could flourish within this culture, speaking its language and wearing its face? He saw that faith possesses an extraordinary flexibility, capable of becoming genuinely Chinese or African or Brazilian without losing its essential character. But this required something most missionaries refused to offer: genuine power-sharing.

Freinademetz poured himself into training Chinese catechists and priests, knowing that foreigners could not sustain a living Church indefinitely. He taught, mentored, and then stepped back, trusting Chinese Christians to lead their own communities even when they made choices he would not have made. This trust was revolutionary and threatening. Fellow missionaries questioned whether Chinese converts were ready for such responsibility. Local authorities suspected his motives. He faced exhausting resistance from multiple directions, enduring loneliness that could have easily turned into bitterness. Yet he remained stubbornly gentle, sustained by a prayer life so deep that it became the oxygen he breathed. His spirituality was not separate from his mission; it was the furnace that kept him going when everything else argued for giving up.

Freinademetz poured himself into training Chinese catechists and priests, knowing that foreigners could not sustain a living Church indefinitely. He taught, mentored, and then stepped back, trusting Chinese Christians to lead their own communities even when they made choices he would not have made

We need his example now more than ever. Our world drowns in cultural anxiety, with people building higher walls and viewing difference as a threat rather than a gift. The Church is not immune to this fear. Too often, we approach other cultures with barely concealed superiority, confident that our particular expression of Christianity represents the only legitimate form. Freinademetz exposes this arrogance as a betrayal of the Gospel itself.

His life insists that a real mission begins with vulnerability. You must listen before you earn the right to speak. You must learn before you presume to teach. You must become part of a community before you can offer meaningful leadership. This terrifies us because it requires surrendering control and admitting we do not have all the answers. It means accepting that God might reveal himself through cultures we initially misunderstand or dismiss.

The practical implications cut deep. Any missionary or cross-cultural minister who is not willing to undergo this kind of transformation should not go. Language learning is not optional decoration; it is the price of admission to genuine relationships. Cultural immersion cannot be superficial tourism where you sample the exotic while maintaining a safe distance. Indigenous leadership development is not charity you dispense; it is recognising that the Church belongs to them as much as to you, perhaps more. And none of this works without profound spiritual depth, the kind that can sustain you when you are lonely, confused, and wondering if you have made a terrible mistake.

Freinademetz understood something we keep forgetting: the Gospel’s universality does not mean uniformity. It means Christianity can speak Mandarin or Swahili or Portuguese with native fluency, expressing eternal truth through infinite cultural variations. The faith is not diminished by this diversity; it is enriched beyond measure. But we only discover this richness when we release our grip on cultural dominance and trust that God is already at work in places we have barely learnt to pronounce.

His legacy challenges every comfortable assumption about mission and evangelisation. It demands we move beyond conquest disguised as compassion, beyond charity that maintains hierarchy, and beyond dialogue that is really monologue with better manners. A real mission looks like Freinademetz, someone willing to be changed by the people he came to serve, someone who discovered that in losing his cultural certainty, he found something infinitely more valuable.

In our fractured world, we need missionaries who build bridges instead of fortresses. We need Christians who view cultural difference as a revelation rather than a problem. We need the courage Freinademetz embodied: the willingness to become genuinely present, to choose partnership over paternalism, and to risk the disorienting transformation that happens when you let another culture reshape your understanding of faith itself.

Father John Singarayar is a member of the Society of the Divine Word, India Mumbai Province,

and holds a doctorate in Anthropology. He is the author of seven books and a regular contributor to academic conferences and scholarly publications in the fields of sociology, anthropology, tribal studies, spirituality, and mission studies. He currently serves at the Community and Human Resources Development Centre in Tala, Maharashtra.